Students of Knowledge and Controversy

Sheikh Salman Al-Oadah

One of the indispensable skills a student of knowledge must have is to be able to gauge the proper value of things

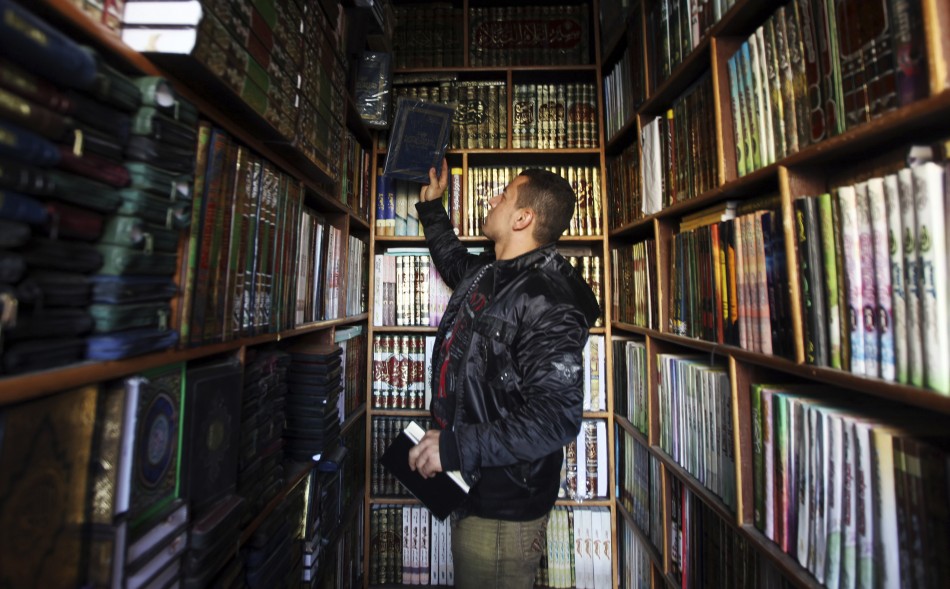

Students of religious knowledge, especially those who focus on Islamic Law, soon become aware of the great variety of opinions and the vast amount of disagreement that exists on most Islamic legal issues.

Students react in different ways. Some try to explain away the differences as being due to a lack of knowledge, believing that with access to the right information, all of these disagreements will just go away. Others becomes suspicious of the scholars and blame disagreements on the vested interests impiety, and insincerity of those who hold certain opinions.

Alas, this is not true.

You will find the most knowledgeable of people, the greatest religious scholars, and the most sincere, unbiased individuals, disagreeing among themselves.

Consider the disagreements that Prophet Muhammad’s Companions had with each other. Even during the Prophet’s lifetime, there were disputes. On one occasion, a feud erupted between the inhabitants of two adjacent neighborhoods in Madinah inhabited the clan of Banu `Amr ibn `Awf.

The Prophet (peace be upon him) spent so much time brokering a reconciliation between them that he was delayed in going to the congregational prayer and Abu Bakr led the prayer instead. (Al-Bukhari and Muslim)

At the time of the Prophet’s death, the Muslims experienced their first great controversy, disagreeing about who should lead them. The native inhabitants of Madinah nominated Sa`d ibn`Ubadah after conferring together in the assembly room of Banu Sa`idah. Afterwards, the Companions all agreed to appoint Abu Bakr as the leader of the Muslims, after they learned that the prophet had instructed that the person to lead them should be from the tribe of Quraysh.

When the wars of apostasy broke out in Arabia during Abu Bakr’s reign, there was considerable disagreement regarding whether it was permissible to fight against all of the breakaway rebel tribes or only those tribes which openly denounced Prophet Muhammad. Abu Bakr was resolved to fight against all the rebellious tribes, and was ultimately able to persuade the other leading Companions, including `Umar, that he was correct in this policy. He there succeeded in uniting the Muslims in the cause against the apostate rebels.

This was the case with a number of crises and challenges that the Muslim community faced during the era of the Companions. At first, they disagreed and then usually in the major issues they were ultimately able to arrive at a consensus. As for disagreements on legal matters and the finer points of religious knowledge where there is no clear or decisive evidence, those disagreements persisted. If disagreement was normal for the best generation of Muslims, how can it not be the case for those who came after them?

Even if we concede – purely for argument’s sake – that sincerity coupled with greater religious knowledge will lead to the resolution of all disagreements, this only assures us that disagreements will be on the rise! People, taken as a whole, will always be subject to incomplete knowledge and to outright ignorance. There will always be those who are weak of understanding, or insincere, or biased.

Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) told us: “Each generation will be better than the one that comes after it, until the day you return to your Lord”. (al-Bukhari)

At the same time, there are some students who have a predilection for controversy, relishing disagreement for its own sake, regardless of whether or not there is a legitimate basis for it. This is also not the right attitude to have. Disagreements cause tension and should not be sought after or capitalized upon for trivial reasons. When someone has a disagreement with a classmate, co-worker, relative, or neighbour on some matter, consider how often it leads to a lawsuit, or to estrangement between them.

People can become part of a controversy simply quoting the opinion of this person and the disagreement of that person. They can become preoccupied with some minor point of debate at the expense of more serious and relevant matters that deserve their attention.

There is a story about the great jurist and legal scholar Ahmad ibn Hanbal which illustrates this point nicely:

A young man named Abu Ja`far Ahmad ibn Habban Al-Qati`i approached Ahmad ibn Hanbal and asked him: ‘Can I perform ritual ablutions with limestone-saturated water?’

Ahmad replied: ‘I dislike this practice’.

The young man then asked: ‘Can I perform my ritual ablutions with the runoff water from soaking beans?’

Again, Ahmad replied: ‘I dislike this practice.’

The young man then asked: ‘Can I perform my ritual ablutions with water infused with safflower?’

Yet again, Ahmad replied: ‘I dislike this practice.’

At this point, the student got up to leave. Ahmad, gently tugged on his shirt to bid him to stay. Then he asked the young man: ‘Do you know the supplication you should say when you enter the mosque?’ The man remained silent. Then Ahmad asked: ‘Do you know the supplication you should say when you leave the mosque?’ Again, the young man could not answer.

Then Ahmad said: ‘Go and learn these things.’

Ahmad showed his understanding of interpersonal dealings politely answering all of the young man’s questions before doing anything else. These questions were all about uncertain matters where no one’s opinion was sure to be correct. They were not essential, inviolable religious teachings.

The way Ahmad answer is quite telling. He chose his words carefully, saying: ‘I dislike this practice.’ This humility is reminiscent of another great jurists way of answering, Abu Hanifah, who used to say: ‘This is my opinion. It is the best I can come up with, if anyone comes with something better, I will give up this opinion for that better one.’

Finally, Ahmad used a very tactful and indirect approach to explain to the young man that it is wrong for a novice student of religion to be preoccupied with controversial trivialities. This is why Ahmad waited for the young man to finish with all of his questions, and then gently tug his shirt when he showed his readiness to leave. He asked the young man relevant questions about the supplications he needed to be aware of.

When the young man could not answer, Ahmad did not scold him. He just told the man that needed to go and learn these things. In this gentlest of ways, Ahmad was actually telling the young man saying: ‘Do not pursue controversial and contentious issues. You are not qualified for that. Busy yourself for the time being with practical matters that will help you practice your faith, until you reach the level of a serious student of religion.’

One of the indispensable skills a student of knowledge must have is to be able to gauge the proper value of things, to know what is important and what is trivial, as the Qur’an says:

And for all things Allah has appointed a due proportion. (At-Talaq 65:3)

_________________________

Source: islamtoday.net.

[ica_orginalurl]